There was a time when having a website was the mark of being serious about your work. Writers had blogs. Photographers had portfolios. Small businesses had landing pages. The website was your corner of the internet, the place you controlled when everything else lived on platforms owned by someone else.

That’s changing, though the shift is quiet enough that you might not have noticed. The creators coming up now—the people just starting to build things on the internet—aren’t reaching for WordPress or Squarespace. They’re thinking in apps.

The Website Was Never Really Ours

To be fair, websites were never as permanent or independent as they seemed. You still needed a hosting company. You still needed a domain registrar. Your site still lived on someone else’s server, subject to their terms and uptime. But there was an illusion of control that mattered. You picked the layout. You wrote the HTML, or at least you could if you wanted to. It felt like building something.

The problem was always reach. A beautiful website that nobody visits is just a file sitting on a server. You needed search engine optimization, social media promotion, email lists—all the machinery that exists outside the site itself. Your website was a destination, but you had to do the work of getting people there.

Apps offered something different: they live on a person’s device. They send notifications. They appear in a list alongside tools people use daily. An app doesn’t wait for someone to remember your URL and type it in. It’s already there, installed, taking up space, asking to be opened.

That proximity matters more than we initially realized.

Apps Feel More Permanent

When you install an app, you’re making a small commitment. You’re giving it storage space. You’re granting permissions. It becomes part of your phone’s ecosystem in a way a bookmarked website never does.

For creators, this changes the relationship with an audience. A website visit is casual, often accidental. Someone clicks a link, reads an article, leaves. There’s no ongoing connection unless they actively choose to return. An app creates a different dynamic. The person has chosen to bring your creation into their daily environment. They’ve integrated it, however slightly, into their routine.

This is why so many businesses that started as websites eventually built apps. It’s not just about features or functionality—though apps can do things mobile browsers can’t—it’s about persistence. An app doesn’t disappear when the browser tab closes.

The Barriers Are Falling

Building an app used to require skills most creators didn’t have. You needed to understand mobile operating systems, programming languages specific to iOS or Android, user interface design for touch screens. Even simple apps required months of learning or the budget to hire developers.

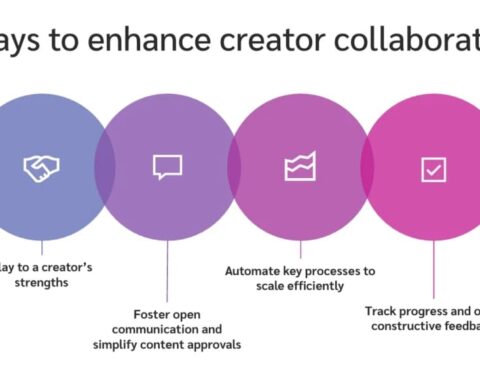

The tools have changed. Modern app builders have emerged that let people create functional apps without writing code. You work through visual interfaces, choosing features and designing screens the way you might assemble a presentation. The platform handles the technical complexity behind the scenes.

More recently, AI has entered the process. Tools like an AI app builder can interpret descriptions of what you want to create and generate the underlying structure. You describe the app’s purpose and features in plain language, and the system translates that into working components. It’s not magic—you still need to make design decisions and understand your users—but the technical barrier has dropped considerably.

This matters for the same reason desktop publishing mattered in the 1980s. When the tools become accessible, the range of creators expands. You get apps from people who understand their specific communities or problems but don’t have computer science backgrounds. A teacher creates an app for classroom management. A community organizer builds a tool for local event coordination. Someone who runs a small bakery makes an ordering app because they understand their customers’ needs better than any developer they could afford to hire.

Expression Through Function

There’s an interesting shift happening in how creators think about their work. A blog post or article expresses an idea through words. A photograph expresses something through composition and light. An app expresses something through what it enables people to do.

The medium is different. You’re not creating content for people to consume; you’re creating capacity for them to act. The app becomes a tool that embodies your understanding of a problem and your approach to solving it.

This isn’t inherently better or worse than other forms of creation—it’s just different. But it’s particularly well-suited to our moment. We’re saturated with content. Another article, another post, another video joins an infinite queue. An app that actually does something, that solves a specific problem or enables a particular activity, cuts through that noise differently.

Consider the creator who builds an app for tracking medication schedules because existing solutions are too complicated for elderly users. The app itself is the statement, the expression. Its simplicity and focus communicate understanding of a real problem. Its existence is the creative act.

Ownership in a Platform World

We’re in an odd period for digital ownership. Social media platforms control most of our online presence. We build audiences on Instagram or TikTok or YouTube, but we don’t own those relationships. The platform can change its algorithm, alter its terms, or disappear entirely, and our work goes with it.

Apps exist in a middle ground. Yes, they’re distributed through app stores owned by Apple and Google. Those companies set rules and take percentages. But the app itself is yours in a way a Twitter account isn’t. You control its function and content. You can migrate it to different stores or distribution methods if needed. The code can be exported and rebuilt.

This matters for sustainability. Creators who depend on platforms are vulnerable to sudden changes. Apps allow for more independence, even if that independence isn’t absolute.

There’s also something to be said for simplicity. A website requires ongoing maintenance—security updates, compatibility checks, broken links to fix. Apps, once built and approved, tend to be more stable. They don’t break when a hosting company updates its servers or a web standard changes. For solo creators without technical support, that stability is valuable.

The Practical Reality

None of this means websites are disappearing or that every creator needs an app. Websites still serve important purposes—they’re indexable by search engines, accessible without installation, and platform-agnostic. For many creators, a website remains the right choice.

But the calculus is changing. Five years ago, “I want to build an app” was an ambitious statement that implied significant resources. Today, it’s increasingly practical for individuals and small teams. The question is shifting from “Can I build an app?” to “Should I build an app?”

The answer depends on what you’re trying to do and who you’re trying to reach. Apps make sense for privacy tools, services, and experiences that people return to regularly. They work well for communities that want a dedicated space apart from general social platforms. They’re suitable for businesses that need direct customer relationships.

Accessibility and Ownership

We’re heading toward a more accessible digital landscape, though not without complications. When creation tools become easier, more people create. That’s democratizing in important ways. Perspectives and solutions emerge from outside traditional technology circles.

But accessibility also means saturation. App stores already contain millions of apps, most of which few people use. Making creation easier doesn’t automatically make success easier.

What we’re really talking about is the ability to try. To have an idea and build it without needing to learn programming or raise funding. To create tools that serve small communities or specific needs that wouldn’t interest larger developers. To own something digital in a world where most of our online presence is rented.

The next generation of creators will build apps because they can. Because the barriers have lowered enough that building an app is becoming as natural as starting a blog once was. They’ll build apps that serve purposes we haven’t thought of yet, using approaches that reflect their particular understanding of the world.

Some of those apps will disappear without trace. Many will serve small groups well. A few might grow into something larger. But the point isn’t success in a traditional sense. The point is that creation—digital creation that does something, that functions, that people can use—is no longer reserved for specialists.

That shift, quiet as it’s been, might be the most significant development in how we make things on the internet. Not because apps are better than websites, but because more people now have the means to build the tools they wish existed.

Read More Gorod